Alamo Master Planners Present New Ideas for the Plaza

Demolish historic buildings and build a modern museum facility. Close South Alamo and East Houston streets to vehicular traffic and create several gated access points. Enhance the tree canopy. Move the Cenotaph less than 500 feet south, as well as sink the original footprint of Alamo Plaza by more than a foot.

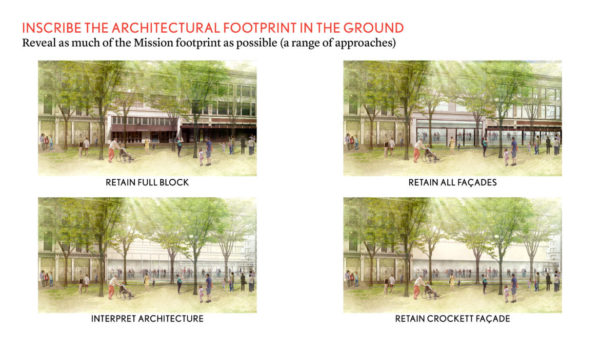

These are just a few of the ideas the Alamo Master Plan design team has proposed in its draft interpretive plan presented to the Citizens Advisory Committee on Thursday evening at the Witte Museum. The $450 million public-private project to reimagine the space in downtown San Antonio would include a “Smithsonian-level” museum and visitor center, interactive exhibits, and more. As presented, the interpretive plan would essentially make the church, Long Barracks, and a portion of the plaza into a destination. This new plan will also feature a pedestrian-friendly green space, and an outdoor extension of the museum with continued public access to the square, designers said.

What most people now think of as Alamo Plaza would become twin plazas and the smaller Alamo Plaza in front of the Church and Long Barracks, and the larger Plaza de Valero reaching southward to Commerce Street. Click here to download a version of the design team’s presentation.

The glass walls proposed in a previous plan are gone. However, the concept of “managed” access to the Alamo Plaza’s mission footprint remains. City Manager Sheryl Sculley said this “managed” access is in order to secure and support programming – such as demonstrations of indigenous cultures, guided tours, and 1836 Battle reenactments – planned for the square.

This “managed” access, which includes moving the free speech/protest zone south along with the Cenotaph to the front of the Menger Hotel, as well as the building demolition and street closures, is expected to generate significant public feedback – and criticism.

During a meeting with the Rivard Report on Wednesday, designers and officials stressed that the renderings shown here and at the Witte and the various concepts and proposals remain works in progress. Public input gathered at a series of hearings over the summer will continue to shape the plan, expected to be finalized this fall.

“The committee is moving in the right direction,” Mayor Ron Nirenberg told the Rivard Report on Thursday. “I haven’t reviewed the plan closely enough to endorse it yet. They have incorporated public feedback, and public access remains crucial.”

The design team consultants – Cambridge, Massachusetts-based landscape architecture firm Reed Hilderbrand; St. Louis-based attraction design firm PGAV Destinations; and London-based museum and heritage consultants Cultural Innovations – have been working with City and Texas General Land Office officials since December 2017 on the interpretive design. It’s aimed at bringing “reverence and learning,” said Reed Hilderbrand principal Eric Kramer, to a plaza that many feel is plagued with cheap commercialization, tourist traps, and lack of historical interpretation and signage.

“We’re still in planning mode,” said John Kasman, vice president of PGAV Destinations. “There’s huge design phases yet to come.”

The latest renderings are the result of public input collected from public meetings. These meetings were held locally and across the state, said Councilman Roberto Treviño (D1), whose district includes the site.

“You’ll see that we’ve been listening,” said Treviño, one of three chairs of the Citizen Advisory Committee and a member of the Alamo Management Committee.

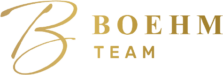

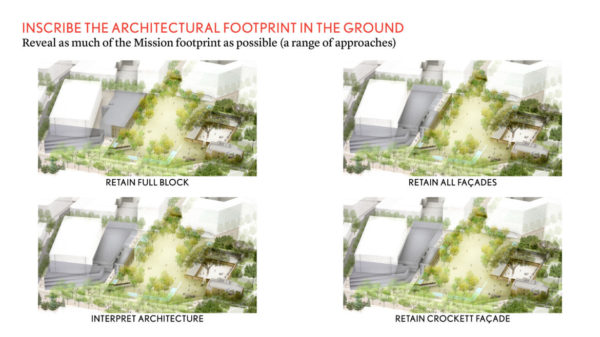

Four public meetings are scheduled in the north, south, east, and west quadrants of the City in June, and more are expected. Demolishing the historic Woolworth, Palace, and Crockett buildings – which the State owns – or perhaps using the shell of one as an entrance to a new facility, are options, Kramer said, but so is keeping them there.

Those are choices that all the various boards, committees, and elected officials associated with developing and executing the plan will have to wrestle with over the next several months in addition to getting public feedback.

Various museum professionals have said the existing buildings, even retrofitted, are not suitable for presenting and preserving museum-quality artifacts. Others are expected to argue that all of the buildings on the plaza’s western flank should be preserved.

The goal for the design is to “change the understanding of the Alamo as a building to the Alamo as a place,” according to the team’s presentation. This most recent effort to revive the plaza started in 2014, and City Council approved the conceptual master plan in May 2017.

Designers translated the guiding principles developed in 2015 by the Citizens Advisory Committee into physical ways to achieve the vision, Kramer said. No easy task, he added, but it boiled down to: revealing as much of the 1700s Mission San Antonio de Valero’s Plaza original footprint, clarifying periods of historic significance, highlighting the importance of water, choreographing visitor approaches to the site, and developing an accessible and coherent place linked to adjacent historic venues.

The designers sought to “remove elements that are not contributing to this experience,” Kramer said. “How do we make this feel like a safe, comfortable, continuous, space?”

That includes a recommendation to relocate the Cenotaph, a 1936 memorial to the Alamo defenders who died in the 1836 Battle, to a space fronting the Menger Hotel where a gazebo currently stands; removing the buildings, which lie directly over the original footprint; exposing the original wall via transparent flooring; digging more than one foot down into the ground to remove modern layers of infrastructure and allow visitors to step down into a distinct, sacred space; and closing the plaza to vehicular traffic to work toward those physical manifestations of the guiding principles, he said.

“The visitor should have a different relationship between the city [built environment] and the mission footprint,” Kramer said, noting that the one-foot drop will achieve a “sense of arrival.”

Moving the 1930s-era Cenotaph is a sticking point for almost all descendants of the defenders who want to see the Cenotaph stay where it is. But moving it less than 500 feet south allows it to have its own space, Kramer said.

“If [the Cenotaph] is moved, it needs to remain on the Alamo grounds in a prominent location,” Nirenberg said. “Most importantly, it needs to be restored so that it doesn’t fall down.”

The proposal includes the establishment of several access points to the plaza’s original footprint that could be sectioned off via railings, fences “hidden” in landscaping, and other barriers yet to be determined. These gates can be opened and controlled by staff and can allow for delivery and emergency vehicles to access the site, Kramer said. The plaza would generally be open 24 hours a day, but the museum, church, long barracks, and garden behind it would close.

Parade routes, as originally proposed, would be redirected to other streets. However, the proposal allows for “flexibility” in routes that could take floats around the back via Bonham or Losoya Street.

Leaders of Fiesta’s Battle of Flowers and Flambeau parades have vehemently opposed adjusting the parade routes moving out of the plaza, as have other residents who see the path in front of the Alamo as a unique and essential tradition to the annual spring festival.

A traffic study conducted by Pape-Dawson Engineers found that the impact of closing portions of East Crockett, South Alamo, and East Houston streets would be minimal, mitigated by turning Losoya Street – a narrow, busy street one block west of the Alamo – into a three-lane, two-way street.

Click here to download a presentation of the study’s findings prepared by Pape-Dawson and presented to the City.

Should planners choose to, demolishing the some or all of the buildings would give the mission footprint, church, and long barracks more visibility. It would also give prominence from within the Alamo Plaza and as visitors approach the space, Kramer said.

Martyn Best, CEO of Cultural Innovations, said a comprehensive study will be commissioned to learn more about the historic relevance of the buildings, their current conditions, and capability of being converted into a world-class museum and/or demolished. The stories of those buildings would be included in the museum as well, he added.

“If you wanted to show [the] original footprint, you could do that inside the building,” said Susan Beavin, president of the San Antonio Conservation Society, which opposes any plan that suggests knocking down any of the three buildings. “There’s no point in not using that [historic] space.”

The Woolworth building is the site of the first peaceful integration of black and white lunch counters in a southern city, Conservation Society Executive Director Vincent Michael added. The lunch counter isn’t there any more, however “that story [and others] needs to be interpreted in the building … there’s a lot of possibilities there.”

Inside the museum, Best said, there would be four galleries that explore life on the Misiòn de Valero site. The 1836 Battle of the Alamo will also be explored. There will also be a gallery that explores the Alamo’s modern journey from “ruins to icon.”

There also would be a “thematic” gallery that explores and debunks the myths associated with the site and battleground. This includes Col. William Barret Travis’ famous “line in the sand” folklore. The mission footprint itself will serve as part of the museum and opportunities for outdoor exhibits and reenactments are plentiful, he said.

No matter the shape or look of the museum, said Douglas McDonald, CEO of The Alamo, “it’s a new academic entity that will challenge us … [and] stretch people’s understanding. That’s the role of museums.”

The City also continues to work with the current tenants of the historic buildings to establish a so-called “entertainment district”. This district would be for businesses such as Ripley’s Haunted Tour and the Guinness World Records to move into.

The move isn’t about discouraging those businesses, Sculley said, “it’s about moving these functions to another place.”

Bryan Preston, director of communications for the Texas General Land Office, said while on tour with the master plan concepts around the state, most Texans’ greatest concern was ensuring the Battle remain the focus of the site and the Cenotaph be preserved.

“Outside of San Antonio, they don’t care about the [smaller details and] issues that we’re all talking about,” Sculley said. “And the donors are not going to come necessarily from here.”

The bulk of the estimated $450 million project will be funded through private donors and philanthropists here, throughout Texas, and across the nation through the nonprofit Alamo Endowment.

“Fundraising won’t happen until there’s a clear plan going forward,” McDonald said, adding that he expects the entire project will be completed by 2023 – before the Alamo’s 300th birthday in 2024.

The Texas General Land Office manages the Alamo and Long Barracks. The City owns the plaza and surrounding streets. The City won’t give up ownership of the streets that run through and around the plaza until the design satisfies the community and stakeholders, Nirenberg has told the Rivard Report. That conveyance of land would require a City Council vote.

Nirenberg sits on the Executive Committee with Land Commissioner George P. Bush. The final interpretive plan would also require approval from both members.

Article Courtesy of Iris Dimmick and the Rivard Report

Alamo Master Planners Present New Ideas for the Plaza

The Boehm Team | (830) 428-8106 | info@MyBoehmTeam.com

Featured Properties

Commerical Properties